Practice Essentials

Dental trauma is relatively common and can occur secondary to falls, fights, sporting injuries, or motor vehicle accidents. Because many clinicians work in a community-based environment where there is no dentist on call for emergencies, they may find themselves forced to deal with acute dental injuries in such situations.

A study sought to determine whether oral cavity cancers occurred more commonly at sites of dental trauma. The study concluded that oral cavity cancers occur predominantly at sites of potential dental and denture trauma, especially in nonsmokers without other risk factors. A key finding of this study was that the location where oral cavity cancers arise is different in smokers and nonsmokers. Recognizing teeth irritation as a potential carcinogen should have an impact on prevention and treatment strategies.

Prevention

A position statement from the National Athletic Trainers’ Association (NATA) recommends that athletic trainers, coaches, and parents should motivate all athletes to wear mouthguards that are properly fitted during any sports activity with an increased risk of orofacial injury.

Clinical evaluation

Initial evaluation of a patient with dental trauma should include the following:

Full physical examination of the head, neck, and face

Assessment of possible injuries to adjacent areas and structures (eg, facial fractures or head and neck trauma)

Imaging modalities that may be considered include the following:

CT of the head, neck, and maxillofacial bones

Periapical radiography

Panoramic radiography of the teeth

See Overview for more detail.

Management

Treatment of dental trauma varies according to the type of injury involved:

Fracture

Avulsion

Luxation (tooth displacement)

Tetanus booster and antibiotics should be administered whenever a dental injury is at risk for infection. Arrangements should be made for prompt follow-up with a dentist or an oral and maxillofacial surgeon.

Dental fractures may be classified as follows:

Ellis class I (superficial enamel only) – No emergency care is required; follow-up with a dentist is arranged as needed

Ellis class II (enamel and dentin, with sensitivity to temperature, air, and palpation) – The exposed dentin is covered, preferably with dental cement; the patient is referred to a dentist within 24 hours

Ellis class III (enamel, dentin, and pulp; a dental emergency) – The fracture is covered with dental cement; patients receive urgent and immediate dental follow-up; topical painkillers increase the risk of infection and thus should not be applied

Root fractures – Extraction of the coronal segment is required; if no more than one third of the root is involved, a dentist may be able to perform a root canal and salvage the tooth

Principles of management for dental avulsions include the following:

An adult tooth that is avulsed should be reimplanted in its socket as soon as possible

If the tooth cannot be reimplanted, it should be placed in a protective solution; it should never be allowed to dry

If the tooth has been dry for a significant period, it should be soaked in the appropriate solution (which depends on the length of the dry period)

Some studies suggest that when a tooth has been out of the mouth for longer than 60 minutes, immediate reimplantation is not required, and a root canal of the tooth should be performed with the tooth outside the mouth before it is reimplanted

After reimplantation, any other injuries are repaired

In children with dental avulsions, primary teeth are never reimplanted, because reimplantation of a deciduous tooth can cause harm to the developing permanent tooth

Luxations may be classified as follows:

Concussion – Mild injury to the periodontal ligament, with some clinical tenderness but no movement of the tooth

Subluxation – More significant injury to the periodontal ligament, with clinical tenderness and movement of the tooth

Extrusion – Partial removal of a tooth from its socket

Lateral luxation – Lateral displacement of a tooth at an angle, with possible fracture of the alveolar bone as well

Intrusion – Impaction of a tooth into its socket in the fractured alveolar bone

Treatment of luxations includes the following:

Concussion and subluxation – A soft diet, administration of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and referral to a dentist; subluxation is a more significant injury and is more often associated with pulpal necrosis

Extrusion – Restoration of the tooth to its original position; splinting

Lateral luxation – Repositioning of the tooth, often made more difficult by a fractured alveolar bone; splinting, done by a general practitioner only if the alveolar bone fracture is minimal and done by a dentist or an oral and maxillofacial surgeon if the fracture is more extensive

Intrusion – Usually, the general practitioner can provide no emergency treatment; referral to a dentist within 24 hours is indicated

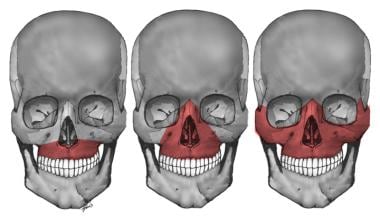

Associated injuries to the maxillofacial bones may be classified as follows:

Le Fort I – Transverse fracture separating the body of the maxilla from the lower portion of the pterygoid plate and nasal septum

Le Fort II – Pyramidal fracture of the central maxilla and palate; facial tugging moves the nose but not the eyes

Le Fort III (ie, craniofacial disjunction) – Facial skeleton completely separated from the skull, with the fracture extending through the frontozygomatic suture lines and through the orbit, the base of the nose, and the ethmoid; on physical examination, the entire face shifts with tugging

The image below depicts the Le Fort classification of maxillary fractures.

Le Fort I, II, and III maxillary fractures.