Practice Essentials

Nephrolithiasis specifically refers to calculi in the kidneys, but renal calculi and ureteral calculi (ureterolithiasis) are often discussed in conjunction (see the images below). Ureteral calculi almost always originate in the kidneys, although they may continue to grow once they lodge in the ureter. The majority of renal calculi contain calcium. The pain generated by renal colic is primarily caused by dilation, stretching, and spasm because of the acute ureteral obstruction.

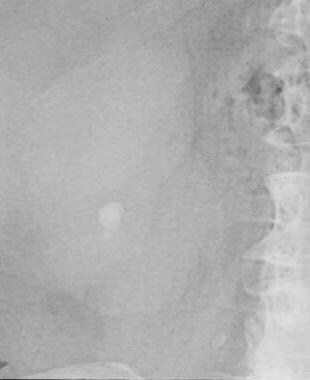

Small renal calculus that would likely respond to extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy.

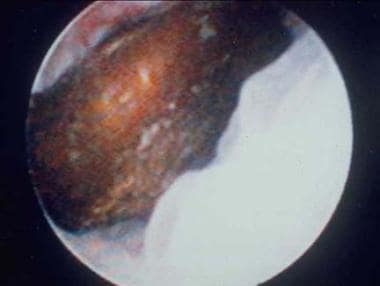

Distal ureteral stone observed through a small, rigid ureteroscope prior to ballistic lithotripsy and extraction. The small caliber and excellent optics of today’s endoscopes greatly facilitate minimally invasive treatment of urinary stones.

Signs and symptoms

The classic presentation for a patient with acute renal colic is the sudden onset of severe pain originating in the flank and radiating inferiorly and anteriorly; at least 50% of patients will also have nausea and vomiting. Patients with urinary calculi may report pain, infection, or hematuria. Patients with small, nonobstructing stones or those with staghorn calculi may be asymptomatic or experience moderate and easily controlled symptoms.

The location and characteristics of pain in nephrolithiasis include the following:

Stones obstructing ureteropelvic junction: Mild to severe deep flank pain without radiation to the groin; irritative voiding symptoms (eg, frequency, dysuria); suprapubic pain, urinary frequency/urgency, dysuria, stranguria, bowel symptoms

Stones within ureter: Abrupt onset of severe, colicky pain in the flank and ipsilateral lower abdomen; radiation to testicles or vulvar area; intense nausea with or without vomiting

Upper ureteral stones: Pain radiates to flank or lumbar areas

Midureteral calculi: Pain radiates anteriorly and caudally

Distal ureteral stones: Pain radiates into groin or testicle (men) or labia majora (women)

Stones passed into bladder: Mostly asymptomatic; rarely, positional urinary retention

See Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of nephrolithiasis is often made on the basis of clinical symptoms alone, although confirmatory tests are usually performed.

Examination of patients with nephrolithiasis includes the following findings:

Dramatic costovertebral angle tenderness; pain can move to upper/lower abdominal quadrant with migration of ureteral stone

Generally unremarkable abdominal evaluation: Possibly hypoactive bowel sounds; usually, absence of peritoneal signs; possibly, painful testicles but normal-appearing

Constant body positional movements (eg, writhing, pacing)

Tachycardia

Hypertension

Microscopic hematuria

Testing

The European Association of Urology (EAU) recommends the following laboratory tests in all patients with an acute stone episode

:

Urinary sediment/dipstick test: To demonstrate blood cells, with a test for bacteriuria (nitrite) and urine culture in case of a positive reaction

Serum creatinine level: To measure renal function

Other laboratory tests that may be helpful include the following:

CBC with differential in febrile patients

Serum electrolyte assessment in vomiting patients (eg, sodium, potassium, calcium, phosphorus)

Serum and urinary pH level: May provide insight regarding patient’s renal function and type of calculus (eg, calcium oxalate, uric acid, cystine), respectively

Microscopic urinalysis

24-hour urine profile

Imaging studies

The following imaging studies are used in the evaluation of nephrolithiasis:

Noncontrast abdominopelvic CT scan: The imaging modality of choice for assessment of urinary tract disease, especially acute renal colic; can determine stone diameter and density

Renal ultrasonography: To determine presence of a renal stone and the presence of hydronephrosis or ureteral dilation; used alone or in combination with plain abdominal radiography

Plain abdominal radiograph (flat plate or KUB): To assess total stone burden, as well as size, shape, composition, location of urinary calculi; often used in conjunction with renal ultrasonography or CT scanning

IVP (urography) (historically, the criterion standard): For clear visualization of entire urinary system, identification of specific problematic stone among many pelvic calcifications, demonstration of affected and contralateral kidney function

Plain renal tomography: For monitoring a difficult-to-observe stone after therapy, clarifying stones not clearly detected or identified with other studies, finding small renal calculi, and determining number of renal calculi present before instituting a stone-prevention program

Retrograde pyelography: Most precise imaging method for determining the anatomy of the ureter and renal pelvis; for making definitive diagnosis of any ureteral calculus

Nuclear renal scanning: To objectively measure differential renal function, especially in a dilated system for which the degree of obstruction is in question; reasonable study in pregnant patients, in whom radiation exposure must be limited

See Workup for more detail.

Management

Pharmacotherapy and supportive care

Medical treatment of acute stone attacks (renal colic) involves supportive care and administration of agents such as the following:

IV hydration

NSAIDs (eg, ketorolac, ketorolac intranasal, ibuprofen)

Nonnarcotic analgesics (eg, acetaminophen [APAP])

PO/IV narcotic analgesics (eg, codeine, morphine sulfate, oxycodone/APAP, hydrocodone/APAP, dilaudid, fentanyl)

Alpha blockers (eg, tamsulosin, terazosin) to facilitate stone passage

Antiemetics (eg, metoclopramide, ondansetron)

Antibiotics (eg, ampicillin, gentamicin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, ofloxacin)

The following drug classes are used for stone prevention/chemolysis:

Uricosuric agents (eg, allopurinol)

Alkalinizing agents (eg, potassium citrate, sodium bicarbonate) – for uric acid and cysteine calculi

Thiazide diuretics – help treat hypercalcicuria

Surgical options

Stones that are 7 mm and larger are unlikely to pass spontaneously and require some type of surgical procedure, such as the following:

Stent placement

Percutaneous nephrostomy

Extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy (ESWL)

Ureteroscopy

Percutaneous nephrostolithotomy (PCNL) or mini PNCL

Open nephrostomy – largely supplanted by less-invasive techniques

Anatrophic nephrolithotomy – for large. complex staghorn calculi that cannot be cleared by an acceptable number of PCNLs; typically done via laparoscopic or robotic approach

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.