Practice Essentials

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is the fourth leading cause of death in the United States and is the leading cause of death in persons aged 1-44 years, with approximately 2 million traumatic brain injuries occurring each year. A National Institutes of Health survey estimates that 1.9 million persons annually experience a skull fracture or intracranial injury. Firearms account for the largest proportion of deaths from traumatic brain injury in the United States; each year, close to 20,000 persons have gunshot wounds to the head.

The definition of a penetrating head injury (pTBI) is a wound in which a projectile breaches the cranium but does not exit it. The morbidity and mortality associated with penetrating head injury remain high. Analysis of the trauma literature has shown that 50% of all trauma deaths are secondary to TBI, and gunshot wounds to the head caused 35% of these.

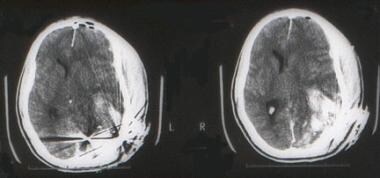

(The CT scan below is of a patient after a gunshot wound to the brain.)

A young man arrived in the emergency department after experiencing a gunshot wound to the brain. The entrance was on the left occipital region. A CT scan shows the skull fracture and a large underlying cerebral contusion. The patient was taken to the operating room for debridement of the wound and skull fracture, with repair of the dura mater. He was discharged in good neurological condition, with a significant visual field defect.

Penetrating head injuries can be the result of numerous intentional or unintentional events, including missile wounds, stab wounds, and motor vehicle or occupational accidents (nails, screwdrivers). Stab wounds to the cranium are typically caused by a weapon with a small impact area and wielded at low velocity. The most common wound is a knife injury, although bizarre craniocerebral-perforating injuries have been reported that were caused by nails, metal poles, ice picks, keys, pencils, chopsticks, and power drills.

In a study of 14 children with intracranial injuries due to spring- or gas-powered BB or pellet guns, 10 of the children required surgery, and 6 were left with permanent neurologic injuries, including epilepsy, cognitive deficits, hydrocephalus, diplopia, visual field cut, and blindness. According to the study authors, advances in compressed-gas technology have led to a significant increase in the power and muzzle velocity of such guns, with the ability to penetrate a child’s skull and brain.

Siccardi et al prospectively studied a series of 314 patients with craniocerebral missile wounds and found that 73% of the victims died at the scene, 12% died within 3 hours of injury, and 7% died later, yielding a total mortality of 92% in this series.

In another study, gunshot wounds were responsible for at least 14% of the head injury-related deaths.

A study using multiple logistic regressions found that injury from firearms greatly increases the probability of death and that the victim of a gunshot wound to the head is approximately 35 times more likely to die than is a patient with a comparable nonpenetrating brain injury.

Evaluation

The assessment of patients with penetrating brain injuries should include routine laboratory tests, electrolytes, and coagulation profile. Many patients have lost a significant amount of blood before reaching the emergency department or might present with disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC); consequently, determining the hemoglobin concentration and platelet count is important. Type and cross match should always be obtained with the initial orders. Obtaining a toxicology screen, including alcohol levels, is also appropriate.

The radiologic methods of evaluation depend on the patient’s condition. In general, a lateral cervical spine and chest radiographs are obtained in the resuscitation room. A CT scan of the head should be obtained as soon as the patient’s cardiopulmonary condition has been stabilized to determine the extent of intracranial damage and the presence of intracranial metallic fragments. The study always should include bone windows to evaluate for fractures, especially when the skull base or orbits are compromised. Some centers can perform CT angiography (CTA) for the evaluation of intracranial and extracranial vessels. Multidetector-row CTA has improved the detectability of both vascular and extravascular injuries in patients with penetrating injuries.

If a vascular injury is suspected and the patient is stable, cerebral angiography often is used to diagnose injuries such as carotid and/or vertebral artery dissections, traumatic pseudoaneurysms, or arteriovenous fistulas.

In patients with penetrating injuries and intracranial metallic fragments, an MRI scan is contraindicated. If the presence of bullets or intracranial metallic fragments has been ruled out, an MRI scan of the brain provides valuable information on posterior fossa structures and the extent of sharing injuries.

A fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) sequence allows the evaluation of contusions or hemorrhages.

Diffusion or perfusion scan sequences are useful to evaluate areas of stroke or cerebral ischemia.

Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) and magnetic resonance venogram (MRV) are useful if vascular or sinus injuries are suspected.

Treatment

Patients with severe penetrating injuries should receive resuscitation according to the Advanced Trauma Life Support guidelines. Specific indications for endotracheal intubation include inability to maintain adequate ventilation, impending airway loss from neck or pharyngeal injury, poor airway protection associated with depressed level of consciousness, and/or the potential for neurologic deterioration. Virtually all individuals with an admission Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) of 8 or less meet these criteria.

The cervical spine is stabilized, and a careful examination for injuries to the neck, chest, abdomen, pelvis, and extremities is performed. A Foley catheter should be inserted, appropriate IV access secured, and volume replacement started.

If pharmacologic paralytic agents were administered during resuscitation, these agents should be reversed in order to complete the neurologic examination. Tetanus prophylaxis is administered.

Propofol, a lipophilic rapid-onset hypnotic with a short half-life that can be titrated to control ICP.

Mannitol administered as intravenous bolus as needed results in decreased ICP; it reduces the viscosity of blood, improving cerebral blood flow; and it might serve as a free-radical scavenger.

If the ICP cannot be controlled, barbiturate coma or a decompressive craniectomy may be indicated.

Additional routine orders include seizure prophylaxis (phenytoin 15-18 mg/kg IV bolus followed by 200 mg IV q12h) and antibiotics.

The following are significant reasons for surgery: (1) to remove masses such as epidural, subdural, or intracerebral hematomas; (2) to remove necrotic brain and prevent further swelling and ischemia; (3) to control an active hemorrhage; and (4) to remove necrotic tissue, metal, bone fragments, or other foreign bodies to prevent infections.