If you have bacteria in your urine but don’t have symptoms of a urinary tract infection (UTI), such as burning or frequent urination, you probably don’t need antibiotics. So why did you get that prescription?

The Infectious Diseases Society of America recommends against antibiotics in this scenario, with exceptions for patients who are pregnant or undergoing certain urologic procedures.

Antibiotics for asymptomatic bacteriuria (ASB) generally do not help; are costly; and can cause side effects, Clostridioides difficile infection, and antibiotic resistance.

Still, antibiotic treatment for asymptomatic bacteriuria remains common, despite guidelines.

And when researchers recently surveyed 551 primary care clinicians to see which ones would inappropriately prescribe antibiotics for a positive urine culture, the answer was most of them: 71%.

“Regardless of years in practice, training background, or professional degree, most clinicians indicated that they would prescribe antibiotics for asymptomatic bacteriuria,” the researchers reported in JAMA Network Open.

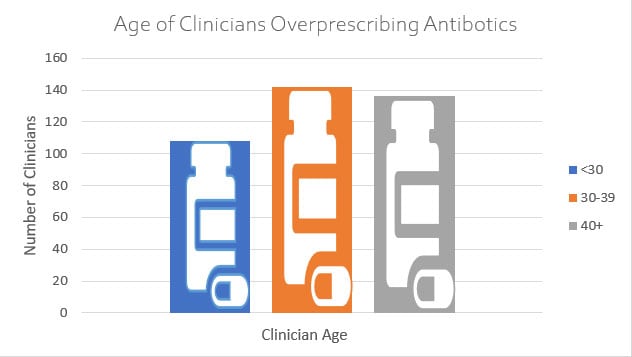

Some groups of clinicians seemed especially likely to prescribe antibiotics unnecessarily.

“Medical maximizers” — clinicians who prefer treatment even when its value is ambiguous — and family medicine clinicians were more likely to prescribe antibiotics in response to a hypothetical case.

On the other hand, resident physicians and clinicians in the US Pacific Northwest were less likely to provide antibiotics inappropriately, the researchers found.

Study author Jonathan D. Baghdadi, MD, PhD, with the department of epidemiology and public health at the University of Maryland and the Veterans Affairs Maryland Healthcare System in Baltimore, summed up the findings on Twitter: ” …who prescribes antibiotics for asymptomatic bacteriuria? the answer is most primary care clinicians in every category, but it’s more common among clinicians who want to ‘do everything.'”

Baghdadi said the gaps reflect problems with the medical system rather than individual clinicians.

“I don’t believe that individual clinicians knowingly choose to prescribe inappropriate antibiotics in defiance of guidelines,” Baghdadi told Medscape Medical News. “Clinical decision-making is complicated, and the decision to prescribe inappropriate antibiotics depends on patient expectations, clinician perception of patient expectations, time pressure in the clinic, regional variation in medical practice, the culture of antibiotic use, and likely in some cases the perception that doing more is better.”

In addition, researchers have used various definitions of ASB over time and in different contexts, he said.

What to Do for Mr Williams?

To examine clinician attitudes and characteristics associated with prescribing antibiotics for asymptomatic bacteriuria, Baghdadi and his colleagues analyzed survey responses from 490 physicians and 61 advanced practice clinicians.

Study participants completed tests that measure numeracy, risk-taking preferences, burnout, and tendency to maximize care. They also were presented with four hypothetical clinical scenarios, including a case of asymptomatic bacteriuria: “Mr Williams, a 65-year-old man, comes to the office for follow-up of his osteoarthritis. He has noted foul-smelling urine and no pain or difficulty with urination. A urine dipstick shows trace blood. He has no particular preference for testing and wants your advice.”

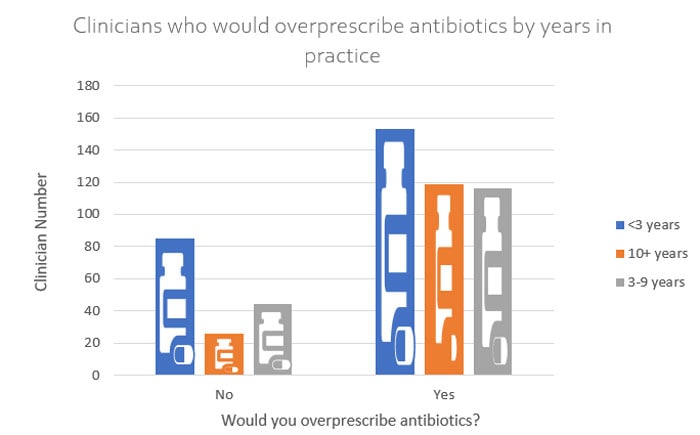

Clinicians who had been in practice for at least 10 years were more likely to prescribe antibiotics (82%) to “Mr Williams” than were those with 3-9 years in practice (73%) or less than 3 years in practice (64%).

Of 120 clinicians with a background in family medicine, 85% said they would have prescribed antibiotics, vs 62% of 207 clinicians with a background in internal medicine.

Nurse practitioners and physician assistants were more likely to prescribe antibiotics (90%) than were attending (78%) and resident physicians (63%).

In one analysis, a background in family medicine was associated with nearly three times higher odds of prescribing antibiotics. And a high “medical maximizer” score was associated with about twice the odds of prescribing the medications.

Meanwhile, resident physicians and clinicians in the Pacific Northwest had a lower likelihood of prescribing antibiotics, with odds ratios of 0.57 and 0.49, respectively.

The respondents who prescribed antibiotics estimated a 90% probability of UTI, whereas those who did not prescribe antibiotics estimated a 15% probability of the condition.

Breaking a Habit

Some prescribers may know not to treat asymptomatic bacteriuria but mistakenly consider certain findings to be symptoms of UTI.

Bradley Langford, PharmD, an antimicrobial stewardship expert with Public Health Ontario, Canada, said in his experience, most clinicians who say they know not to treat ASB incorrectly believe that cloudy urine, altered cognition, and other nonspecific symptoms indicate a UTI.

“The fact that most clinicians would treat ASB suggests that there is still a lot of work to do to improve antimicrobial stewardship, particularly outside of the hospital setting,” Langford told Medscape.

Avoiding unnecessary antibiotics is important not just because of the lack of benefit, but also because of the potential harms, said Langford. He has created a list of rebuttals for commonly given reasons for testing and treating asymptomatic bacteriuria.

“Using antibiotics for ASB can counterintuitively increase the risk for symptomatic UTI due to the disruption of protective local microflora, allowing for the growth of more pathogenic/resistant organisms,” he said.

One approach to addressing the problem: Don’t test urine in the first place if patients are asymptomatic. Virtual learning sessions have been shown to reduce urine culturing and urinary antibiotic prescribing in long-term care homes, Langford noted.

Updated training for health care professionals from the outset may also be key, and the lower rate of prescribing intent among resident physicians is reassuring, he said.

A Role for Patients

Patients could also help decrease the inappropriate use of antibiotics.

“Be clear with your doctor about your expectations for the healthcare interaction, including whether you are expecting to receive antibiotics,” Baghdadi said. “Your doctor may assume you contacted them because you wanted a prescription. If you are not expecting antibiotics, you should feel free to say so. And if you are asymptomatic, you may not need antibiotics, even if the urine culture is positive.”

The study was funded by a grant from the National Institutes of Health, and Baghdadi received grant support from the University of Maryland, Baltimore Institute for Clinical and Translational Research. Coauthors disclosed government grants and ties to Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, Vedanta Biosciences, Opentrons, and Fimbrion. Langford reported no relevant financial conflicts of interest.

JAMA Netw Open. Published online May 27, 2022. Full study

For more news, follow Medscape on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube