Lloyd I. Sederer, MD: Welcome. I’m Dr Lloyd Sederer. Today I’m joined by Dr Donald Berwick, senior fellow at the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, and Dr Esther Choo, an emergency physician and professor at the Oregon Health & Science University, for something we’re calling COVID Conversations.

We’re discussing how healthcare workers are affected by COVID at home and with their families, because the impact of this pandemic doesn’t stop at the end of a shift; it’s everywhere.

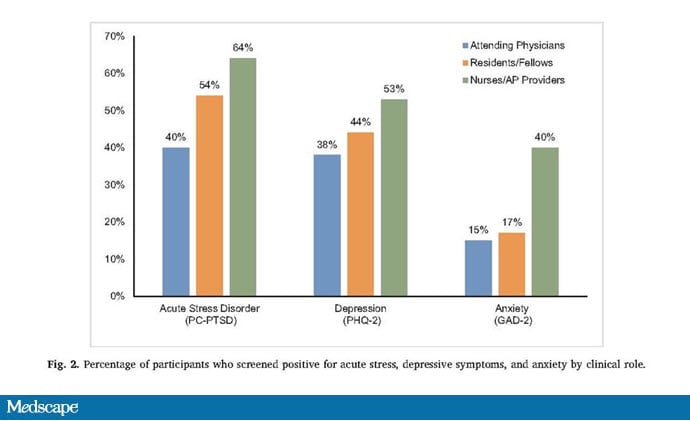

A recent article published in General Hospital Psychiatry detailed the mental health effects among healthcare workers in New York City during COVID-19. Principal among these effects were fears of making family members and friends ill. How do clinicians bear that, and what must they do to avoid infecting their loved ones?

Esther Choo, MD, MPH: Speaking from the point of view of the clinical setting, this is something that has evolved. When we were in the first wave, we had no idea how much transmission there was going to be from the hospital to the home. You saw people do these really elaborate rituals: exchanging clothing, showering head to toe before they left the hospital, taking off all their jewelry and their wedding rings. We weren’t sure how much risk was conveyed by small things that got caught somewhere on you, and if that was going to be the way you took it home to your families.

It was a combination of uncertainty at the hospital and then fear for yourself, worried that you were going to get sick, worried that your colleagues were sick and were going to transmit it to you, and then that you would take it home to your families. That was a huge driver in terms of the anxiety and the fear.

I think a lot of us felt, It’s fine for me. I’ll go in. This is what I signed up for, and I understand there is risk. There was risk before COVID with patients who had infectious diseases. We have risks of all kinds in the emergency department. We face agitated patients and family members. There’s always a little bit of violence against healthcare workers, baseline risks you know about. But the idea that your job would then expose your family to greater risk added something potentially devastating.

Sederer: I’ve heard that some doctors and nurses are staying apart from their children to keep them safe. How are you helping loved ones understand that this distance is awful but it’s necessary?

Choo: There are so many elements to it. I think a lot of family members feel like they’re taking part in the pandemic effort by being more supportive at home. I have a husband who’s also in healthcare but is not in high contact with patients overall; he’s a radiologist. He understood that he’s going to pull more than his weight at home and that’s how he’s supporting the people in the emergency departments and the intensive care units. I think there was a lot of that. And I know my friends’ nonmedical spouses were also saying things like, “Go, do what you need to do, and I’ll keep everything okay here.”

That was something that felt tolerable in the short term, yet as this pandemic has gone on I think we’ve all really needed to pull on family members, rotate roles, and adjust that. That’s fine for a month or two, but to have someone say they’ll take care of everything at home for a year is not sustainable. I do think it put a huge strain on relationships as well. Our families were really kind of the invisible part of this pandemic effort.

Sederer: Don, are there ways you know of by which the whole family learns to cope with these stresses and demands?

Donald M. Berwick, MD, MPP: As in any healthy family relationship, communication is everything. My main window into this is through my daughter, who’s a hospitalist at a medical center. She has an 11-year-old and a 4-year-old, as well as a husband who works full time but not in healthcare. I’ve witnessed all of the renegotiation of time, childcare, and tasks that’s gone into that.

Meanwhile, the kids are under stress. The 11-year-old has not been able to go to school. He’s been virtually educated, and that’s very, very difficult for someone his age.

Another new source of stress is the use of space. They’re cooped up in their house. It requires negotiation and communication and openness.

There are other considerations with multigenerational families. At my age, I’m considered higher risk, which has completely changed the way that I can — or mostly cannot now — help support with grandchildren and care. I’m working full time also, but not in a patient-facing context. This disruption of normal multigenerational interactions has been very profound.

I must also note that we’re privileged. In the end, we can afford the childcare, to take time off. But there are millions and millions of Americans, in healthcare and outside healthcare, who are reeling because they have been placed at a disadvantage by social determinants of health, structural racism, and poverty or near poverty in a country that has not gotten its act together on that.

It’s like every single one of the instructions that we give are laughable when faced with the reality of people’s lives.

Sederer: What can healthcare institutions do for those without the same privileges, who don’t have the same level of financial security or family support, yet they have to work to maintain their home?

Berwick: COVID is raising some very important questions as to what kind of country we are. Do we have a sense of solidarity, support, compassion, especially for people who find themselves at a disadvantage, mostly not at all through their own fault? Do we regard policies of redistribution, generosity, and outreach as fundamental for everybody? That needs to be in the form of public policy, with laws, regulations, and public expenditures that will reach out and support people when they need it. We have something like 40 million people with food insecurity right now, 17 million hungry children during COVID, which we should not allow.

Sederer: Esther, are there practical things being put in place at your institution to help relatively underprivileged healthcare workers, such as free childcare for those with younger children or educational supports?

Choo: There are some. I think we were not as prepared to support the entire workforce in these things. Exactly as Don says, this is making us all stop and think about who has the luxury of things like childcare or paid sick leave, where you can afford to take time out to follow public health recommendations around quarantine or isolation if you get sick.

Sometimes I’ll tell patients that if they’re waiting for a COVID-19 test result, they’ll need to take a certain amount of time from work, isolate in their homes, etc. My patients practically laugh, because they can either stay home from work or they can feed their families. Their families will go hungry before they’re able to see if maybe they have COVID and they might get sick from it. They live in homes where multiple people are sharing rooms, and they ask, “How would you like us to isolate, exactly?” Or they’re taking care of their elderly parents. Should they just neglect the chronically ill parent at home? It’s like every single one of the instructions that we give are laughable when faced with the reality of people’s lives.

Sederer: In some ways, all of this is a harbinger of the world ahead where we have an aging population, this huge gap between the privileged and those without enough money or who must live in neighborhoods that are not safe. It’s a glimpse into the kind of social problems that are not just related to COVID.

Don, has that come up in some of your conversations with other clinicians?

Berwick: All the time. The alarm bell on this issue of inequity has never been louder.

Of course, anybody in health services research, like all three of us, knows that this is no surprise. Data about disadvantage and its consequences for health are not new. We have a century of data about that and a public and private regime that has not solved it.

COVID’s underlining it. It’s putting a big exclamation point after it. I think it actually brings our country, our professions, and our healthcare organizations to a moment of choice, because even if COVID is over sooner rather than later, what are we going to do? Is this something where we’re going to say “never again” and do something about it, or lament it and move on? I hope we get leadership at all levels to close these very, very costly gaps.

At the organizational level, there are things that can be done. I think we need to take a hard look at ourselves. There are 1.4 million healthcare workers who get paid so little that they’re on Medicaid, and 700,000 of their kids are on Medicaid. There are a million healthcare workers who don’t have health insurance. This is institutional and it needs reconsideration.

Sederer: While the big support needs to come federally, that’s not enough. Things have to happen locally as well, in communities and families, and in hospitals in terms of closing those gaps to enable people to have a life. It’s been said that the measure of society is how it treats its poor and vulnerable. That’s not been a good measure to look at in recent years.

Berwick: To be honest, Lloyd, we have to zoom out to the global context here. This surge that is hurting our country so badly is being experienced in other low- and middle-income countries already at levels that are very tragic. I think we’re going to have to make some decisions about global resource allocation and global equity, or we’re turning our back on something too important.

Sederer: What information can you trust and what kind of leadership is needed now to take us toward a better world than we’ve been in?

Berwick: There are many levels to answering that question. I think we can begin with perhaps the easiest, which is science. Public confidence in science has been shaken, partly because it’s been shaken intentionally at national leadership levels. But we have wonderful, reliable science in this country. We need to return to a mature dialogue with the public about what science can and can’t do so that we can get past that.

You look at the magic of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or the National Institutes of Health, or even the World Health Organization, which we need to build back up. Political leadership is needed. If there’s any rule about pandemics or global crisis, it’s that communication has to be consistent, confident, honest, open, and clear. If we return to that, we stand a chance of getting farther along.

Sederer: Those are all the principles of post-disaster leadership as well, and COVID is certainly a disaster. Esther, what are your thoughts about this?

Choo: I agree that that kind of messaging and consistency from the top is so clearly needed.

I also think that there are so many lessons from the vaccine era of the pandemic, because we’re finding that in the absence of a strong, centralized national message, we’re now really leaning on local experts and trusted people. In some ways, I really think the success of vaccine uptake is going to be out of our hands. Instead, it’s happening on a micro level because people are turning to their trusted local representatives, whether it’s a single physician, a faith leader, or a well-known person. On a national level, it just seems like it’s a circus out there in terms of our elected officials, where there’s a lot of performative stuff happening that has much more to do with politics than science. So people are looking to those that they feel like they have a relationship with, a person they’ve seen on TV locally for 20 years, to local affinity groups, for that information. The challenge now is identifying those people and making sure that we’re building out the vaccine efforts on the ground.

Sederer: We know that there’s a whole community of those with what we call “vaccine hesitancy,” whether it’s the flu vaccine or even the measles vaccine, which has contributed to the resurgence of measles worldwide and death of children. What are you seeing now along those lines as the vaccine begins to become available?

Choo: There is the whole anti-vax movement, which has tremendous energy and power. Their success is due to the fact that they have a sustained message and a big community. I think there’s very little we can do about that. That’s a bigger long-term problem.

What we’re really grappling with during this pandemic is not that there is hesitancy, but rather almost earned mistrust. We’ve invested hundreds of years into not having trust between the medical establishment and, in particular, brown and Black communities of color. You don’t earn back trust over a matter of months in an acute crisis, unfortunately.

This is where we have to do things differently. We’ve had months to plan for this, and I don’t know if we’ve taken advantage of that time. We really have to relinquish the lead, I think, and turn to the leaders and the scientists from the communities that we’re trying to reach, empower them, and amplify their message. Because I can tell you that if you look across the leadership of the pharmaceutical companies who are making the vaccines or the ivory tower where we are testing them, those are not really the communities that inspire trust, unfortunately. There’s a mismatch there. I think we’re kind of sowing the seeds of many, many decades of mistrust and racialized abuses.

Sederer: We’ll need to rebuild that trust locally with diverse people of influence. Don, what are your thoughts on this?

Berwick: I’m hoping for a sense of “planfulness.” I think the incoming national leadership realizes that we’ve got to have a sense of direction, honesty, openness, and a plan. That will really help.

I think that we need to invest in science, just as Esther said. We can navigate our way out of this, but only with facts.

And maybe it’s just a fantasy, but I must say that I aspire to a sense of American solidarity where we say, “We’re going to beat this thing together. We can’t do it by beating each other,” and that ability to recruit a spirit of wholeness.

Sederer: And understanding each other’s point of view. There’s so much division. You can’t fix what you don’t know. We have to be much more open than we’ve ever been to understand why people take the positions they do.

Berwick: This is a very clever virus. It’s got a lot of patience. It’s going to wait us out, so to stop it we’re going to have to come together.

Sederer: But we are resilient and we have unprecedented science that we’ve seen this past year. We do have the spirit as a country, and that’s what we’re all betting on and hoping for.

Let me thank you both for your participation, wisdom, and experience. You’ve been watching COVID Conversations, a collaboration between BongoMedia and Medscape. I hope you’ll join us for future episodes. Thank you.

Donald M. Berwick, MD, MPP, is president emeritus and senior fellow at the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, and one of the nation’s leading authorities on healthcare quality and improvement. In July 2010, President Barack Obama appointed Berwick to the position of Administrator of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, which he held until December 2011. Berwick has served as clinical professor of pediatrics and health care policy at the Harvard Medical School, and is now lecturer in the Department of Health Care Policy at Harvard.

Esther Choo, MD, MPH, is a professor in the Center for Policy and Research in Emergency Medicine at Oregon Health & Science University. She is a practicing physician and popular science communicator. Choo writes a regular column on healthcare inequalities for The Lancet while also serving as a CNN medical analyst.

Follow Medscape on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube