Overview

Background

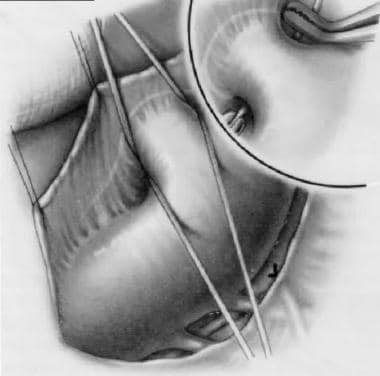

Patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) is a persistent communication between the descending thoracic aorta and the pulmonary artery that results from failure of normal physiologic closure of the fetal ductus (see the image below). In most individuals, the ductus arteriosus is located on the left side; however, if a right aortic arch is present, the ductus arteriosus may be located on the right or left side. The ductus arteriosus is very rarely bilateral.

Patent ductus arteriosus.

In normal fetal circulation, the unexpanded lungs receive only 5-8% of the blood entering the pulmonary artery. The ductus arteriosus serves as the predominant route of circulation passing through the right ventricle and pulmonary artery. Approximately 55-60% of the systemic circulation passes from right to left through the ductus.

In the fetus, the oxygen tension is relatively low because the pulmonary system is nonfunctional. This, coupled with high levels of circulating prostaglandins, acts to keep the ductus open. The high levels of prostaglandins result from the little amount of pulmonary circulation and the high levels of production in the placenta.

At birth, the placenta is removed, eliminating a major source of prostaglandin production, and the lungs expand, activating the organ in which most prostaglandins are metabolized. In addition, with the onset of normal respiration, oxygen tension in the blood markedly increases. Pulmonary vascular resistance decreases with this activity. These events result in contraction of the smooth muscle within the wall of the ductus, which results in its closure.

A preferential shift of blood flow occurs; the blood moves away from the ductus and directly from the right ventricle into the lungs. Until functional closure is complete and pulmonary vascular resistance is lower than systemic vascular resistance, some residual left-to-right flow occurs from the aorta through the ductus and into the pulmonary arteries.

In normal-birth-weight and full-term neonates, the ductus arteriosus closes within 3 days after birth. However, the ductus arteriosus is patent for more than 3 days after birth in 80% of preterm neonates weighing less than 750 g, and its persistent patency is associated with increased morbidity and mortality. Furthermore, in the presence of a significant left-to-right ductal shunt in low-birth-weight neonates, a decreased peripheral perfusion and oxygen delivery occurs.

Although PDA is frequently diagnosed in infants, it may not be discovered until childhood or even adulthood. In isolated PDA, signs and symptoms are consistent with left-to-right shunting. The shunt volume is determined by the size of the open communication and the pulmonary vascular resistance. PDA may exist with other cardiac anomalies, which must be considered at the time of diagnosis. In many cases, the diagnosis and treatment of a PDA is critical for survival in neonates with severe obstructive lesions to either the right or left side of the heart.

Surgery is the mainstay of treatment for PDA.

Two forms of surgical therapy are performed: the traditional surgical approach, which entails a thoracotomy (or alternatively, thoracoscopy), and catheter closure.

The future of PDA repair lies in further development of more sophisticated catheter methodologies to facilitate closure. Currently, the Rashkind device and the Gianturco coils are most promising. As catheters shrink, the procedure may become appropriate in infants, and the traditional surgical approach may be used in premature patients and those in whom catheter approach is not possible.

The future of pharmacologic therapy in the closure of a PDA remains undetermined. The medical approach depends on a better understanding of the factors that precipitate closure of the ductus and of ductal histology.

Indications

In infancy, congestive heart failure is an indication for closure of the PDA. If medical therapy is ineffective, urgent intervention to close the structure should be undertaken. Repair may be delayed in the patient who is asymptomatic or well controlled on medical therapy. All PDAs should be closed because of the risk of bacterial endocarditis associated with the open structure. Over time, the increased pulmonary blood flow precipitates pulmonary vascular obstructive disease, which is ultimately fatal.

If an infant has failed to thrive or has overt congestive heart failure, the ductus should be interrupted, regardless of age and size. If the patient is asymptomatic, elective ligation and division can be carried out at approximately age 4 years when the risks of intubation are decreased and the child is more capable of understanding the procedure and process. Some authorities recommend closure any time after age 12 months or when the patient becomes symptomatic.

Contraindications

Relatively few contraindications to closure of a PDA are recognized. The primary contraindication to repair is severe pulmonary vascular disease. If transient intraoperative occlusion of the PDA does not decrease elevated pulmonary arterial pressures with a subsequent increase in aortic pressure, then the closure must be undertaken carefully and may be contraindicated. Closure of the ductus does not reverse preexisting pulmonary vascular disease.

A subset of associated cardiac anomalies—so-called ductal-dependent lesions—depend on flow through the PDA to maintain systemic blood flow. Premature closure of the ductus without concurrent repair of the following defects is contraindicated and may be fatal:

Pulmonary artery hypoplasia

Pulmonary atresia

Tricuspid atresia

Transposition of the great arteries

Aortic valve atresia

Mitral valve atresia with hypoplastic left ventricle

Severe coarctation of the aorta

In these patients, all attempts should be made to preserve ductal flow until a more permanent palliative shunt can be constructed or definitive repair can be undertaken.

Contraindications to catheter closure currently involve the size of the patient. Very small premature infants still require surgical closure. Contraindications to surgical closure include concurrent uncontrolled sepsis and an inability of the patient to tolerate general anesthesia.

Outcomes

The prognosis is generally considered excellent in patients in whom the PDA is the only problem. The mortality from surgical closure is less than 0.5%. No deaths have been reported from catheter closure; however, patients undergoing this procedure are part of a select group and have a generally good prognosis otherwise.

If additional cardiac anomalies are present, the risk increases. A high risk is reported in the presence of associated lesions, increased pulmonary vascular resistance, or when the ductus is calcified or aneurysmal.

In premature infants who have other sequelae of prematurity, these sequelae tend to dictate prognosis of PDA. Studies have shown that preterm babies with a gestational age of 30 weeks or younger had a 72% rate of spontaneous closure of PDA. In addition, 28% of children with PDA who were conservatively treated (with prophylactic ibuprofen) reported a 94% closure rate. This rate compared well with rates reported in literature following medical treatment (80-92%). Surgical mortality in premature infants ranges from 20% to 41%.

In the adult patient, prognosis is more dependent on the condition of the pulmonary vasculature and the status of the myocardium if congestive cardiomyopathy was present before ductal closure. Patients with minimal or reactive pulmonary hypertension and limited myocardial changes may have a normal life expectancy.