Practice Essentials

Wilms tumor, or nephroblastoma, is the most common solid renal mass and abdominal malignancy of childhood, with a prevalence of 1 case per 10,000 population.

Conversely, it is very rare in adults, with an incidence rate of less than 0.2 per million per year.

The tumor (see the images below) occurs in both hereditary and sporadic forms, and approximately 6% are bilateral.

Most are unicentric and arise from the kidney. Extrarenal Wilms tumors (EWTs) are rare and most commonly found in the retroperitoneal space (44.4%) and the uterus (14.8%).

The results of treatment of Wilms tumor have improved in recent years, reaching 4-year overall survival in the favourable histology group of nearly 90%.

The most common clinical presentation involves an asymptomatic abdominal mass with insidious growth. Secondary hypertension may be observed in as many as 25% of patients as a result of increased renin levels. Initial ultrasonography is commonly performed, and sonograms demonstrate a smooth, well-defined mass of renal origin with uniform echogenicity.

Preferred examination

Although modern imaging techniques such as color Doppler sonography, helical or multidetector-row CT, and MRI have substantially improved the potential to image Wilms tumors, definitive diagnosis is still based on histology. Children presenting with abdominal masses initially undergo ultrasonography scanning, usually in combination with chest radiography. Initial diagnosis of a Wilms tumor is generally based on ultrasonography supplemented with Doppler ultrasound because inferior vena cava (IVC) tumoral thrombi are occasionally missed on CT; missing these thrombi can lead to a fatal outcome at surgery.

If a Wilms tumor is suspected or if the primary tumor is histologically confirmed, it should be staged by using CT or MRI. The tumors may be large, and their size may make it difficult to identify its renal origin on sonograms. Therefore, CT and MRI may be useful for distinguishing between renal tumors and adrenal tumors. Radiologists prefer chest CT over chest radiography to stage the spread of disease to the thorax.

In a study of ultrasound and laboratory findings in Wilms tumor survivors with a solitary kidney, signs of kidney damage were seen in 22 of 53 (41.5%) patients on ultrasonography. The most frequently detected abnormalities were hyperechoic rings around renal pyramids (28.3% of patients). Hypertrophy of the solitary kidney occurred in 71,7% of cases.

Conventional radiography is inexpensive and noninvasive; however, it has low sensitivity and specificity. A chest radiograph may miss lung metastases. Regarding CT and MRI, sedation or general anesthesia may be required. MRI is expensive and has certain contraindications; for example, claustrophobia may be a problem. Neither CT nor MRI is tissue specific, and tissue diagnosis may be required. Bone scintigraphic studies are highly sensitive but lack specificity.

Performing chest CT to stage a Wilms tumor can be justified only if following conditions are met

:

If the information obtained is reliable

If the CT findings are correlated with the patient’s prognosis

If the CT results alter treatment from what would have been recommended in their absence

If the information obtained with CT favorably influences the therapeutic outcome

The main objectives of staging Wilms tumors are the following:

To identify the origin of the tumor

To assess the extent of the tumor

To assess involvement of the renal vascular pedicle

To detect regional lymph node metastases

To detect bilateral Wilms tumors

To detect distant metastases

CT or MRI fulfills these objectives well. Although CT of the chest may be included in the primary staging procedure, most investigators from international studies of Wilms tumors have relied on chest radiographs to detect lung metastases.

Angiography is now uncommonly performed, but it may be useful in the preoperative assessment of tumors in patients with a solitary kidney or bilateral Wilms tumors. Likewise, inferior venacavography is now seldom performed, as magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) and Doppler imaging studies may provide the same information noninvasively.

Radionuclide studies may be indicated for assessing the volume of functioning renal tissues by using technetium-99m dimercaptosuccinic acid (DMSA). The findings may provide guidance as to what tissues may be preserved when nephron-sparing surgery of bilateral tumors is being contemplated. Isotope renography is a sensitive technique for assessing renal function.

Positron emission tomography (PET) may be important in the future. Bone scintigraphy is useful for evaluating only clear cell sarcoma, which tends to metastasize to bone.

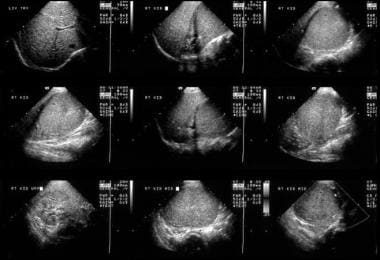

This 6-year-old male child with hematuria was referred for a renal ultrasound scan. The scan shows a 6 x 8 cm solid mass at the lower pole of the right kidney displacing part of the collecting system in a cephalad direction. The mass is of uniform echogenicity with a vague small central hypoechoic area suggestive of tumor necrosis.

An IVU shows a nonfunctioning left kidney with a suggestion of ill-defined mass in the left loin due to a biopsy-proven Wilms tumor. Note the functioning right duplex renal collecting system. The chest radiograph in the same child shows a lung metastatic deposit (arrow). Images courtesy Dr. Pedro Daltro and Dr. Edson Marchiori, Port Allegre, Brazil. edmarchiori@gmail.com

Axial US image shows a solid 4.5-cm solid mass anterior cortex, lower pole of the left kidney. Image courtesy of Dr. Pedro Daltro and Dr. Edson Marchiori, Port Allegre, Brazil. edmarchiori@gmail.com

Surgical resection is mandatory for treatment and staging, with all patients receiving chemotherapy. Radiation therapy is reserved for managing residual abdominal tumors or hematogenous metastatic disease. In the past 3 decades, the survival rate has been a remarkable 90% with a multidisciplinary approach to this tumor. Radiologic diagnosis, staging, and follow-up are crucial for therapeutic success. About 15% of treated patients have relapses of Wilms tumor, with most occurring within 2 years after nephrectomy and only occasionally after 5 years.

Surgical staging

Wilms tumors are usually staged by using the method suggested in the National Wilms Tumor Studies (NWTS), in which the tumors are classified for surgery into V stages, as described below.

Stage I

The stage I tumor is confined to the kidney and is completely excised. The renal capsule is intact. No evidence of tumor at or beyond the resection margins is noted. The tumor is not ruptured, or it was sampled during biopsy (excluding fine-needle aspiration biopsy) before its surgical removal. The vessels of the renal sinus are free from disease.

Stage II

The stage II tumor extends beyond the kidney and is completely excised. The renal capsule or renal sinus may be invaded. The renal vascular pedicle may contain tumor. The tumor was previously sampled during biopsy (except for fine-needle aspiration biopsy), or the tumor spilled before or during surgery, but the spillage was confined to the renal fossa and does not involve the peritoneal surface. No evidence of tumor at or beyond the resection margins is noted.

Stage III

In stage III tumor, residual nonhematogenous tumor is present after surgery, and the tumor is confined to the abdomen. Any of the following situations may occur:

Lymph node findings in the abdomen or pelvis are positive.

The tumor penetrates the peritoneal surface, or implants are found on the peritoneal surface.

Tumor cells are found at the margin of surgical resection on microscopic examination.

Tumor spills beyond the flank before or during surgery.

Stage IV

In stage IV, there are hematogenous metastases—involving, for example, the lung, liver, bone, and brain—or lymph node metastases outside the abdominopelvic region.

Stage V

In stage V tumor, bilateral renal tumoral involvement is present.

Differential diagnosis

Renal blastema and/or nephroblastomatosis

Renal blastema and nephroblastomatosis are interrelated conditions closely related to Wilms tumors. The persistence of primitive renal blastema beyond infancy (4 mo) is abnormal except in small microscopic rests. Large amounts of primitive blastema remaining in sheets in the cortex or in discrete nodules are termed nephroblastomatosis.

Ultrasonographic detection is possible, but sonography lacks the sensitivity of CT and MRI. On sonograms, the affected kidney may be enlarged and lobulated with multiple hypoechoic areas. Corticomedullary differentiation may be lost.

After such findings are discovered, 3 monthly ultrasound examinations should be performed to detect their progression to a Wilms tumor. Rapid growth of any of the hypoechoic rests suggests progression. Antenatal detection is possible when sonograms reveal bilateral nephromegaly with normal renal echogenicity. However, foci of calcification may be associated with polyhydramnios, and they can occur as a part of a familial condition.

Mesoblastic nephroma

Mesoblastic nephroma is the most common congenital renal neoplasm. It is a solitary hamartoma, and it is usually benign and unilateral. Sonograms show mesoblastic nephroma as a complex mass that may contain cystic areas. A Wilms tumor may also appear as a multiloculated mass. Antenatal diagnosis is possible. On sonograms, mesoblastic nephroma is seen as a large, solitary, predominantly solid, coarse, and echogenic renal mass that may contain cystic areas. It may be associated with polyhydramnios.

Clear cell sarcoma

Clear cell sarcoma is a distinct histologic entity that accounts for 4% of the renal tumors observed in childhood. These tumors usually cannot be differentiated from Wilms tumors on images. Clear cell sarcoma is not associated with any other somatic abnormality. Overall, the prognosis is poor compared with that of patients with Wilms tumors. Since bone metastases may occur with this disease, bone scintigraphy or FDG-PET is recommended.

Rhabdoid tumor of the kidney

The term rhabdoid is derived from the microscopic appearance of the tumor cells that resemble muscle cells. Rhabdoid tumors make up around 2% of renal neoplasms and are more common in infancy than in any other period. An association with brain tumors, especially medulloblastoma, has been described. The brain tumors may precede or appear several years after the detection of this tumor. Brain MRI is needed a part of the workup of rhabdoid tumors.

Like other neonatal masses, rhabdoid tumor of the kidney can be diagnosed in utero. In neonates, detection may follow their presentation with an abdominal mass, hypertension, or hypercalcemia. The age at presentation overlaps with that noted for congenital mesoblastic nephroma. The clinical and imaging characteristics of rhabdoid tumors of the kidney are similar to those of congenital mesoblastic nephroma, clear cell sarcoma, and Wilms tumor. Therefore, specific diagnosis is usually not possible. One important differentiating point is that clear cell sarcoma of the kidney and rhabdoid tumor of the kidney are invariably unilateral.

The prognosis for patients with a rhabdoid tumor of the kidney is much worse than that of patients with other renal tumors.

Intrarenal neuroblastoma

Abdominal neuroblastomas usually develop in the retroperitoneum. Most arise from the adrenal gland and displace the kidney inferomedially. In rare cases, a neuroblastoma may mimic a Wilms tumor, arising from tissues in the kidney or invading the kidney. To make diagnosis complicated, rare neuroblastomas possess other features more typical of Wilms tumor than of intrarenal neuroblastomas.

Epithelial nephroblastoma

Epithelial nephroblastomatosis, or cystic Wilms tumor, is less malignant than Wilms tumor and may appear cystic or papillary. In its benign form, it gives rise to a multilocular cystic renal disease. Ultrasonographic and CT findings do not help in predicting the degree of malignancy.

Multicystic dysplastic kidney

Multicystic dysplastic kidney is a relatively rare condition. Even so, it is the most common cause of abdominal masses in neonates, leading to 50-65% of renal masses in infancy.

Multicystic dysplastic kidney is a developmental anomaly due to atresia of the upper third of the ureter. In most cases, concomitant atresia affects the renal pelvis and infundibula. The underlying obstruction usually occurs at or before 8-10 weeks of life. Obstruction occurring at a stage later than this gives rise to a relatively rare combination of renal dysplasia and hydronephrosis.

About 33% of patients have contralateral renal anomalies, such as multicystic dysplastic kidney, pelviureteric junction (PUJ) obstruction, hypoplasia, and rotational anomalies. When ureteric duplication is encountered on the contralateral side, one of the ureters may be atretic, with associated segmental renal dysplasia.

Ultrasonography demonstrates a large unilateral renal mass with 10-20 cysts but sometimes as many as 50 cysts of various sizes. Islands of dysplastic renal tissue may be observed between the cysts, but no normal tissue is seen. Antenatal diagnosis is possible. Ultrasonographic findings can help in differentiating multicystic dysplastic kidney and hydronephrosis from other conditions in infants, such as Wilms tumor, neuroblastoma, mesoblastic nephroma, and adrenal hemorrhage.

Autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease

Autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease, also known as infantile polycystic disease, is thought to result from dysplasia of the upper collecting system and/or collecting tubules, leading to cysts of various sizes. Microdissection studies have shown fusiform sacculations and cystic diverticula of the distal portions of collecting tubules and collecting ducts, while the proximal collecting tubules are diffusely dilated.

The condition is inherited in an autosomal recessive manner, and it is usually present in infancy or childhood, though it may be diagnosed in utero by means of ultrasonography. Disease severity is usually greatest in patients who present early.

Renal involvement is bilateral, but it may be asymmetric. Autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease is associated with hepatic fibrosis and ductal hyperplasia, which may cause portal hypertension. In the context of this disease, death is usually caused by renal failure in the youngest children and by hepatic failure in older children.

The disease may be divided according to the patient’s age at presentation, as follows:

Prenatal form: this form appears in infants, it is rapidly fatal, and it involves 90% of the renal tubules.

Infantile form: about 60% of the tubules are involved. The child has uremia but survives longer than those with the prenatal form.

Young-childhood form: Affected children present with hypertension and chronic renal failure. Approximately 25% of the renal tubules are involved.

Late presentation, juvenile form: symptoms are usually related to hepatic fibrosis, portal hypertension, and GI hemorrhage; in these late cases, small cysts are sometimes seen in the renal cortex.

Ultrasonography shows diffusely enlarged kidneys with a generalized increase in echoes produced by the innumerable fluid–tubular wall interfaces. The renal borders are poorly defined, and corticomedullary differentiation is lost. Echogenicity of the liver is frequently increased.

The peripheral cortex may be spared because it does not have collecting ducts. This feature is found in infants who do not have severe disease and who are likely to survive infancy. However, in severely affected infants, images may show a peripheral sonolucent halo, which may represent markedly dilated ectatic tubules near the renal surface. When high-resolution probes are used, imaging shows a radial array of ectatic and dilated tubules of 1-2 mm in diameter. In utero, the normal combined renal circumference is 27-30% of the abdominal circumference. In infantile polycystic disease, this circumference increases to 60%, a feature that allows for prenatal diagnosis.

Simple renal cysts

The exact etiology of simple renal cysts is uncertain. These lesions may be retention cysts due to obstruction, or they may arise in embryonic rests. Simple renal cysts are uncommon in children, being found in 2-4% of pediatric postmortem examinations. However, their frequency increases with age, and they are found in 50% of adults older than 50 years.

Simple cysts are usually asymptomatic unless they are complicated by hemorrhage or infection. Their mass effect may be large. The cysts arise in a parapelvic position and compress part of the renal collecting system. On sonograms, the cysts are entirely free of echoes, with good sound transmission. They give rise to distal acoustic enhancement. The cyst has a smooth outline without a demonstrable wall. Small cysts may appear echo-free only when they are in the focal zone of the ultrasound beam because of partial-volume affects. Cysts smaller than 3 mm in diameter cannot be identified in the parenchyma.

Ultrasonography is more accurate than CT for visualizing the internal septae and for demonstrating the internal morphologic features of the cyst. If the nature of a cyst identified during sonography is in doubt, follow-up scanning or aspiration of the cyst should be performed. If the appearance is classically that of a simple cyst, no further action is needed.

Multilocular cystic nephroma

Multilocular cystic nephroma is synonymous with multilocular renal cyst, cystic Wilms tumor, hamartoma, cystic adenoma, polycystic nephroblastoma, Perlman tumor, and segmental multicystic kidney. These confusing terms indicate the uncertainty about the etiology and about whether the lesion is dysplastic, neoplastic, or hamartomatous. If a Wilms tumor is noted in the walls of this tumor during histologic analysis, it is often treated as a Wilms tumor.

In terms of its morphologic characteristics, a multilocular renal cyst forms a well-defined, bulky mass arising at the lower pole or between poles of an otherwise normal-looking kidney. The mass has a fibrous capsule, which may contain smooth muscle and cartilage. The tumor mass itself has multiloculated, noncommunicating cysts separated by fibrous tissue. The tumor often protrudes into the renal pelvis, and approximately 50% become calcified.

Some researchers have postulated that focal failure of a ureteral branch to organize this segment of the metanephric blastema gives rise to the appearance just described. Undifferentiated mesenchymal tissue in the various constituents of the fibrous capsule supports the postulate that multilocular cystic nephroma is a type of renal dysplasia.

The ultrasound appearance of a multilocular renal cyst is that of a bulky renal mass with a conglomerate of cysts separated by thick septa protruding into the renal pelvis. Calcification is detected in some masses.

Renal hematoma

Subcapsular hematomas spread around the kidney, giving rise to an echogenic rim. Focal subcapsular hematomas may cause depression of the cortex. As the hematoma resolves, fibrosis may occur, compressing the kidney and resulting in hypertension.

Intrarenal hematomas are more frequently hypoechoic than renal contusions and subcapsular hematomas. Echogenic hematomas may be lost in the central echo complex. Renal hematomas may enlarge; therefore, they should be followed up because they may cause delayed rupture of the kidney.

Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome

Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome may be associated with omphalocele (12% of cases) and organomegaly. The incidence of hemihypertrophy, renal anomalies, Wilms tumor, and hepatoblastoma is increased. Antenatal diagnosis is possible.

Heredofamilial features of cystic dysplasia

Cystic renal dysplasia is a component of several familial syndromes. Renal cysts have been described in association with more than 50 syndromes. These include the trisomies, von Hippel-Lindau disease, Jeune syndrome (asphyxiating thoracic dystrophy), Meckel-Gruber syndrome, short rib–polydactyly syndrome, Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome, and holoprosencephaly.

WAGR syndrome

WAGR syndrome (Wilms tumor, aniridia, genitourinary abnormalities, mental retardation) is a rare genetic disorder characterized by a de novo deletion of 11p13.

Hydronephrosis

The renal collecting system forms a part of the central echogenic complex, and it is frequently not identifiable as a separate structure. Visualization of the collecting system depends on the rate of urine formation and drainage. Slight dilatation of the collecting system is a common normal finding during diuresis or when the bladder is full. In these cases, the dilatation resolves when the bladder is emptied.

Hydronephrosis is simply dilatation of the renal collecting system. This is not always due to obstruction, and in the converse, obstruction does not always cause hydronephrosis. Hydronephrosis is seen as anechoic fluid in the renal collecting system and pelvis separating the echoes of the central sinus. In long-standing cases, images may show secondary thinning of the renal parenchyma. Dilated calyces lose their sharp, angular margins and become blunted.

When hydronephrosis is considerable, the entire collecting system is outlined as a series of connected fluid-filled channels. When part of the renal collecting system is dilated, the condition may superficially resemble a Wilms tumor on sonographic examination, but close inspection can easily differentiate the 2 conditions.

Renal cell carcinoma

Renal cell carcinoma is a primary epithelial neoplasm that arises from the proximal convoluted tubule. Nearly all cases occur in adults, though the carcinoma has been recorded in children younger than 10 years. Early cases are seen as small, cortical-based masses that enlarge and invade the renal parenchyma. Late cases may cause a classic triad of loin pain, flank mass, and hematuria. Approximately 5% of patients have bilateral tumors, though not usually simultaneously.

Appearances vary widely and depend on the size of the tumor, which may be solid, cystic, or complex. Solid tumors transmit sound waves poorly; therefore, acoustic transmission is unchanged or decreased compared with that of a normal kidney. The most common appearance is increased echogenicity, which corresponds to areas of increased vascularity seen on angiography. Small tumors are particularly echogenic, so small angiomyolipomas cannot be distinguished on sonograms.

Small, hyperechoic renal cell carcinomas may have a hypoechoic rim caused by the tumoral pseudocapsule, and it may contain small, anechoic areas. No true capsule is present, and the tumor margins are irregular. Large tumors tend to hypoechoic. About 6-20% show evidence of calcification.

Denys-Drash syndrome

Denys-Drash syndrome is a rare entity associated with male pseudohermaphroditism, gonadal dysgenesis, progressive glomerular disease, diffuse mesangial sclerosis, renal failure, and nephroblastoma.