Overview

Gastroschisis represents a herniation of abdominal contents through a paramedian full-thickness abdominal fusion defect. The abdominal herniation is usually to the right of the umbilical cord. No genetic association exists. A gastroschisis usually contains small bowel and has no surrounding membrane. The herniated bowel is not rotated and is devoid of secondary fixation to the posterior abdominal wall.

Gastroschisis occurs 1 in 2000 births and is ordinarily detected during prenatal ultrasound scans. Fetal outcome varies from uncomplicated surgical correction to stillbirth or neonatal death. Early markers on ultrasound indicating increased mortality include abdominal circumference less than 5th percentile and an abnormal gastric bubble.

(See the images below.)

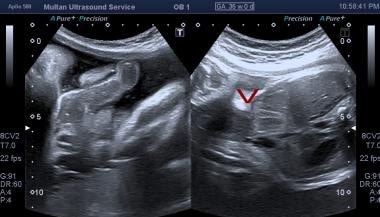

Axial sonogram through the mid to upper abdomen. This image shows free-floating exteriorized bowel in relation to the anterior abdominal wall. S = stomach; V = spine.

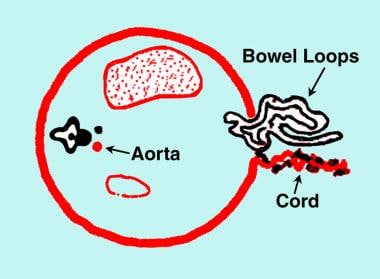

Diagram of the transverse section of the fetal abdomen showing gastroschisis. Note the bowel herniation in the right paramedian/paraumbilical region. The cord is inserted in the normal location to the left of the herniation. No membranous covering exists over the herniated bowel.

Ultrasound of fetal abdomen showing anterior wall defect.

Because the herniated bowel is bathed by amniotic fluid, both maternal serum and amniotic fluid alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) levels are elevated, more so than in exomphalos. Thus, gastroschisis is found incidentally or because of an elevated maternal AFP level, a finding in 77-100% of cases. Rarely, polyhydramnios may prompt an antenatal sonographic examination. Fetal growth restriction is a frequent association. Oligohydramnios is rare. Chromosomal anomalies are not associated with gastroschisis, and familial occurrence is exceptionally rare.

Gastroschisis usually is detected in the second trimester using antenatal sonography.

The diagnosis can often be made by using antenatal sonography before 20 weeks’ gestation. With transvaginal sonograms, the diagnosis has been made as early as 12 weeks’ gestation.

In early pregnancy, the bowel loops can be seen floating in the amniotic fluid. The thickness and the diameter of the bowel are normal. Later in pregnancy, bowel obstruction, peritonitis, bowel perforation, and fetal growth restriction may occur. Intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) occurs in 38-77% of fetuses and is usually secondary to nutrient loss through exposed bowel. Approximately 48% of infants with gastroschisis are small for their gestational age.

A bowel diameter greater than 17 mm usually represents significant bowel dilatation, and diameters greater than 11 mm are usually associated with a greater number of postnatal bowel complications. Sonographic findings of bowel abnormalities are associated with difficult abdominal wall repair and an increased incidence of complications.

Approximately 50% of fetuses with gastroschisis are small for their gestational dates. Fetal abdominal circumference, which is regarded as a standard reference for assessment of fetal size, does not apply to this group of fetuses; therefore, obstetric management may be difficult.

The mortality rate of gastroschisis is approximately 17%. Surgical repair should be offered within the first day after delivery to avoid infection. The outcome is no different in infants delivered in tertiary obstetric centers than in infants delivered in smaller peripheral hospitals, although delivery within easy access of a neonatal surgical unit is advised. Cesarean delivery is performed in many mothers of fetuses with gastroschisis, although this does not convey any advantage over vaginal delivery.

A recent meta-analysis by South and associates has shown that the overall incidence of intrauterine fetal death (IUFD) in gastroschisis is much lower than previously reported. The largest risk of intrauterine IUFD occurs before routine and elective early delivery would be acceptable. The analysis has concluded that the risk for IUFD should not be the primary indication for routine elective preterm delivery in pregnancies that are affected by gastroschisis.

Preferred examination

Antenatal sonography is the key imaging examination available, with detection rates of 70-72%. Prenatal sonography is the primary imaging modality in pregnancy because it is noninvasive, is rapid, and allows real-time fetal examination. Plain radiographs and bowel contrast studies may be indicated in the postnatal postoperative period to assess bowel complications.

In studies exploring the association between antenatal ultrasound signs and outcomes in gastroschisis, significant positive associations were identified between intra-abdominal bowel dilatation (IABD) and bowel atresia, polyhydramnios and bowel atresia, and gastric dilatation and neonatal death. No other ultrasound sign was significantly related to any other outcome.

With the use of antenatal sonography, the diagnosis of a surgically treatable malformation is made before birth in an increasing number of fetuses. This allows fetal intervention, in utero transfer, planned delivery in a specialized unit, and antenatal counseling of the parents regarding the likely prognosis and outcome.

Limitations of techniques

Sonography remains operator dependent, and artifacts are a problem. Despite the straightforward nature of the defect, a diagnosis of gastroschisis can be missed.

Misdiagnosis of exomphalos as gastroschisis has occurred in 5% of patients. This misdiagnosis has serious implications because exomphalos is often associated with chromosomal and other severe anomalies and karyotyping is not performed in patients with gastroschisis.

In one case series, gastroschisis was misdiagnosed as exomphalos at a rate of 14.7%. This misdiagnosis results in unnecessary amniocentesis, which exposes the fetus to the risks involved in amniocentesis and which also exposes the mother to psychological trauma.

Assessment of fetal size by using abdominal circumference measurements is difficult in the presence of gastroschisis. Postnatal plain radiographs and bowel-contrast studies lack specificity and expose the infant to a radiation burden. However, Siemer et al have developed a sonographic weight formula for fetuses with abdominal wall defects.

The authors evaluated their formula in a group of 97 fetuses with either gastroschisis or omphalocele and concluded that it provided a significantly greater accuracy in estimating fetal weight than a more commonly used formula. More data will be necessary to determine the utility of Siemer et al’s formula.