Overview

Rathke cleft cysts (RCCs) are benign, epithelium-lined intrasellar cysts believed to originate from remnants of the Rathke pouch. RCCs commonly have a round, ovoid, or dumbbell shape. They are found in 13-33% of the general population and can compress adjacent structures, causing symptoms such as headaches, vision problems, or pituitary hormone deficits.

Studies have shown that the majority of radiologically diagnosed RCCs remain unchanged or decrease in size over time, suggesting that, in the absence of pressure symptoms, conservative management is a reasonable approach.

The description of RCC has expanded since the advent of computed tomography (CT) scanning and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

See the images of Rathke cleft cyst below.

T1-weighted sagittal image obtained before contrast enhancement depicts a well-marginated sellar mass, a Rathke cleft cyst, extending into the suprasellar cistern. Note that the mass has homogeneous high signal intensity relative to the brain parenchyma.

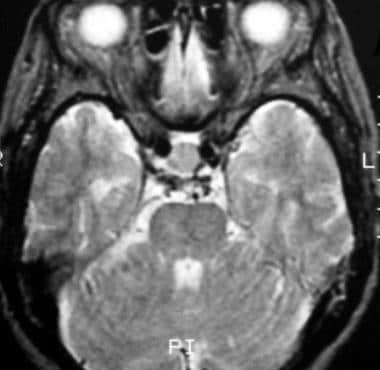

T2-weighted axial image shows the mass, a Rathke cleft cyst, is isointense relative to the cortex. (This image was obtained in the same patient as in the previous image.)

After contrast enhancement, no significant enhancement is seen in the Rathke cleft cyst. Note the normally enhancing pituitary infundibulum dorsal to the mass. (This image was obtained in the same patient as in the previous 2 images.)

Pathophysiology

As Voelker and colleagues have stated, the most common theory about the origin of RCCs is that the cysts are derived from true remnants of the embryologic Rathke pouch.

On or about the 24th day of embryonic life, the Rathke pouch arises as a dorsal diverticulum from the stomodeum; it is lined with epithelial cells of ectodermal origin. At approximately the same time, the infundibulum forms as a downgrowth of the neuroepithelium from the diencephalon. By the fifth week, the Rathke pouch comes into contact with the infundibulum, and the neck of the pouch becomes occluded at the buccopharyngeal junction. During the sixth week, the Rathke pouch separates from the oral epithelium. Subsequently, the pars distalis of the pituitary gland develops from the anterior wall of the pouch. The posterior wall does not proliferate and remains as the poorly defined pars intermedia.

The residual lumen of the pouch is reduced to a narrow Rathke cleft, which generally regresses. The persistence and enlargement of this cleft is considered to be the cause of the RCC.

Other authors have different theories regarding the formation of RCCs, suggesting instead that the cells of origin are derived from the neuroepithelium or the endoderm, or that they come from metaplastic anterior pituitary cells.

Anatomy

On pathologic examination, the size of the cyst can vary from 2-40 mm. The cystic capsule frequently is described as thin and has been reported as being transparent, blue, gray, white, yellow, pink, red, tan, or green. The cystic fluid commonly is thick or gelatinous, but it also can be watery, serous, or similar in consistency to motor oil. The cystic fluid most often is yellow, but it also has been described as white, clear, gray, or green.

At histologic examination, the cysts typically are composed of vascularized stroma of connective tissue and 3 types of epithelial cells: ciliated, nonciliated epithelial, and mucous secreting. Nonciliated cells appear as a single layer of flat cells or as stratified columnar cells. Fager and Carter concluded that the presence of ciliated epithelial and mucous-secreting cells in a pituitary gland is pathognomonic for RCC.

In a retrospective analysis, Shin and co-authors found that all the RCCs studied were intrasellar in origin at their primary location.

Because of their cystic nature, most of the RCCs that were studied expanded into the suprasellar cistern through the cleft of the diaphragma sella.

In Voelker’s report, a retrospective study of 155 patients with symptomatic RCC, the cyst was found in intrasellar and suprasellar locations in 71% of the patients.

The sella was enlarged in 80%.

Presentation

RCCs often produce no symptoms and so are usually discovered incidentally, when radiographic or necropsy findings are reviewed. Most cysts are smaller than 2 cm in diameter. Symptomatic RCCs are uncommon, but cysts can enlarge and cause symptoms secondary to compression of the pituitary gland, pituitary stalk, optic chiasm, or hypothalamus.

Symptomatic RCCs vary in presentation. In a study of 11 symptomatic patients by Rao and colleagues, 8 patients initially had visual symptoms.

In another study, by Eguchi and co-authors, visual symptoms occurred in 47% of patients.

Signs and symptoms included reduced visual acuity, optic atrophy, visual field defects, and a chiasmatic syndrome. Eguchi’s study looked at 19 patients, 4 of whom had diabetes insipidus, 3 of whom had amenorrhea and/or galactorrhea, and 2 of whom had panhypopituitarism. With systematic endocrinologic examinations, various degrees of pituitary dysfunction were observed. Other abnormal findings included headaches and, less commonly, epilepsy.

In the study by Voelker and colleagues, the most common finding was pituitary hypofunction with multiple endocrinopathies.

Younger patients, aged 4-22 years, had evidence of hypopituitarism from an early age, with resultant growth retardation. The second most common symptom was visual disturbance, which included visual field defects resulting from chiasmatic compression. The next most common symptom was headache, of which 57% were frontal. Shin and co-authors described impotence or low libido as the most common endocrine abnormality in men; in women, the most common was hyperprolactinemia. Many RCCs are associated with pituitary adenomas.

In addition to the symptoms described above, endocrine symptoms occur as a result of the adenoma.

Other unique or unusual findings associated with RCC include pituitary apoplexy,

hypophysitis, giant cysts, large frontal extension with an unusual shape, aseptic meningitis, intracystic abscess, sphenoid sinusitis, and empty sella syndrome.

Preferred examination

MRI is the modality of choice in the detection of RCCs.

Thin-section sagittal and coronal MRI scans should be obtained through the sella. CT scans are also useful for evaluating RCCs. They are particularly helpful in delineating associated bony remodeling and in assessing calcification.

Limitations of techniques

MRI is superior to CT scanning for evaluating RCC mass extension. Sagittal and coronal MRI scans provide reliable information concerning the relationship of the mass to the optic nerves, optic chiasm, and hypothalamus. Coronal MRI is also helpful in the evaluation of the lateral extension of the sellar cyst and its relationship to the internal carotid arteries and cavernous sinuses. MRI also has superior multiplanar capabilities and contrast resolution compared with those of CT scanning.

The advantage of CT scanning is that it is superior to MRI in depicting small amounts of calcium. This advantage can be important, because the presence of calcification tends to indicate an alternative diagnosis, such as craniopharyngioma, although small calcifications are observed in some cases of RCC.

CT scanning is also superior to MRI in the evaluation of associated bony remodeling.

Other problems to be considered

Pituitary adenomas (cystic) can be included in the differential diagnosis of a Rathke cleft cyst. Only rarely do they occur simultaneously, with only 32 reports in the literature of a pituitary adenoma and concomitant Rathke cleft cyst.

In such cases, presenting complaints included hormonal symptoms, visual disturbances, and headache.

Treatment

The most common approach in the treatment of RCCs is transsphenoidal surgery, in which the cyst is partially excised and drained.

This method is effective and helps to preserve pituitary function. Radical excision can cause additional and unnecessary pituitary damage; therefore, it is not the treatment of choice. In transsphenoidal surgery, the cyst is opened, a biopsy specimen is obtained from the wall, and the cyst is drained into the sphenoid sinus. No sellar reconstruction is needed unless a CSF leak is noted during surgery. In patients in whom this approach is not appropriate because of an inaccessible cyst, craniotomy is performed, usually via a right frontal flap.

In some patients, the postoperative follow-up period ranges from 1 week to 26 years (average, 34 mo). The postoperative outcome for most patients is resolution of or improvement in symptoms. In patients with hypopituitarism or diabetes insipidus, the RCC usually fails to improve. After surgery, the greatest improvement in symptoms occurs with a resolution of neurologic symptoms (71% of patients), followed a resolution of ophthalmologic symptoms (70% of patients). In more than 65% of patients, amenorrhea, galactorrhea, and oligomenorrhea improve. Headaches and visual field defects resolve in 82% and 70% of patients, respectively.

Surgical complications include CSF rhinorrhea (7% of patients), diabetes insipidus (4% of patients), and meningitis (4% of patients). A rare surgical complication noted by Baskin was nasal septal perforation.

Abscess formation in a cyst is a treatable complication; this complication should be considered even in the absence of fever when radiologic features suggest the condition. Treatment with surgery and antibiotic medications is effective in most patients.

The recurrence rate after craniotomy is twice as high as that after transsphenoidal surgery. In addition, leakage of the cystic contents into the subarachnoid space has been reported; this can cause aseptic meningitis. In cases of recurrence, extensive removal of the cyst wall is most appropriate, and some recommend external beam pituitary radiation therapy, although its role in preventing further recurrence remains unclear. Fager and Carter recommend full evacuation of the cystic contents and liberal opening of the wall in the treatment of symptomatic RCCs.

When this procedure is performed, recurrence is rare.

An interesting aspect of treatment is the decrease in the size of the cyst after high-dose steroid therapy. Although the pathophysiologic mechanism is not clear, the steroids are assumed to have an effect on the secretion or absorption of cystic fluid. This finding suggests that steroid therapy may be useful in some patients with an RCC and inflammatory changes. Further study in this area is needed to gauge its effectiveness is the treatment of RCCs.

Another surgical option could be an endoscopic endonasal approach to remove an intrasellar or suprasellar Rathke cleft cyst, under direct visual control, in order to identify and preserve the pituitary hypophysis.

This approach may also serve to improve postoperative outcome by avoiding nasal packing and possible breathing difficulties.