Practice Essentials

Cysticercosis is an infection caused by the eggs of Taenia solium, or pork tapeworm. It is the most common parasitic infestation affecting the central nervous system (CNS), and approximately 90% of patients with cysticercosis have CNS involvement. When the CNS is involved in cysticercosis, it is called neurocysticercosis (NCC). The pathogenesis and clinical presentation vary with the site of infection and the host immune response. NCC poses a complex diagnostic and treatment dilemma because of its varied presentation. Factors determining treatment include whether symptoms are present, the location of the cysts, and whether there is a host immune response.

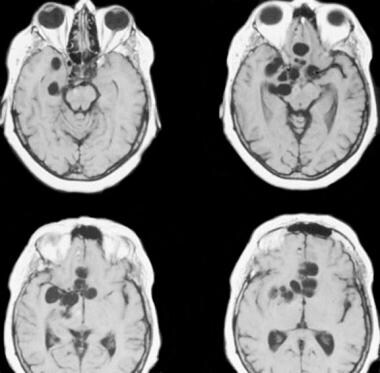

(See the CNS images of cysticercosis below.)

Nonenhanced CT scan of the brain demonstrates the multiple calcified lesions of inactive parenchymal neurocysticercosis.

CT images of the brain in a patient with neurocysticercosis show numerous parenchymal lesions.

MRIs of the brain show multiple, large, cysticercus cysts in the basal cisternal spaces in a patient with neurocysticercosis.

NCC is recognized as a common cause of neurologic disease in developing countries, and it is also seen in developed countries, including the United States. NCC is a chronic disease associated with substantial morbidity and high social and economic costs. A minimal estimate of annual treatment costs in the United States (a country in which NCC is not endemic) is $9 million; in Mexico and Brazil, costs are estimated to be nearly $90 million per year.

Types of NCC

There are 4 types of NCC:

Meningeal (racemose variety)

Parenchymal (solitary or multiple cysts)

Ventricular (usually solitary)

Mixed

Meningeal cysts form mostly in the basal meninges, sometimes causing stroke and hydrocephalus. Parenchymal cysts are usually found in the cerebral cortex, including the cortical-subcortical junction. The white matter is rarely involved. Ventricular cysts are seen in 15% of patients with NCC; in 50% of cases, they are located in the fourth ventricle.

They may cause intermittent hydrocephalus. In approximately 20% of cases, parenchymal cysts are found concomitantly with intraventricular cysts.

When cysticerci become inflamed, the granular ependymitis and accompanying fibrillary astrocytosis cause the cysticerci to adhere to the walls of the ventricles. The racemose form is characterized by proliferative lobulated cysts without a scolex; such cysts are usually found in the ventricular system and the subarachnoid space. Although infrequent, this is the most serious manifestation of NCC.

Spinal cord cysts are rare (1-3% of cases). Intramedullary NCC occurs from either hematogenous or ventriculoependymal spread. In two thirds of patients, the thoracic cord is affected.

Ocular involvement is seen in approximately 5% of patients; it may be diagnosed by means of fundus examination or ultrasonography (US). Cysts may float freely in the anterior/vitreous chamber of the eye or adhere to retinal and subretinal tissues. Subretinal cysts produce vasculitis and retinal edema. If located in the vitreous, cysts result in chorioretinitis and vitreous detachment; they rarely occur in the eyelids or lacrimal glands.

Stages of NCC

The host may tolerate the worm as long as the embryo is alive. Viable cysticerci are associated with minimal inflammation (vesicular stage). The worm usually dies 2-6 years after infection, and the disintegration of the parasite triggers a vigorous tissue reaction. An inflammatory response to the degenerating cyst results in severe symptoms.

As the cysticerci lose the ability to control the host’s immune response, the cyst wall becomes infiltrated and is surrounded by predominantly mononuclear cells. Inflammatory cells enter the cyst fluid (colloid stage). As the host’s immune response progresses, fibrosis encompasses the cysticercus, with concomitant collapse of the cyst cavity (granular-nodular stage). The dead parasite decays into eosinophilic desiccated material.

The final stage is a calcified nodule, which presumably forms as a result of dystrophic calcification of the necrotic larva (calcific stage). The various pathologic states that may be seen in NCC include the following:

Meningoencephalitis

Granulomatous meningitis

Ocal granuloma

Focal or diffuse multiple cysts

Hydrocephalus

Intraventricular cysts

Ependymitis

Arteritis

In India, NCC is characterized by small, multiple, diffuse parenchymatous involvement. In Latin America, NCC is characterized by solitary or few large parenchymal cysts, meningeal racemose, and the ventricular involvement.

Preferred examination

The diagnosis of cysticercosis of the CNS (neurocysticercosis, NCC) is complex; no diagnostic test identifies all cases of cysticercosis. The diagnosis depends on a constellation of the clinical history, exposure history, laboratory results, and imaging findings. CT scanning or MRI after the intravenous administration of contrast material is the imaging test of choice.

A negative serologic result does not exclude cysticercosis. When inflammation is absent, enzyme-linked immunotransfer blotting (EITB) results are negative in 60-80% of patients. Results are probably negative in more than 80% of cases of NCC involving only a single lesion. The sensitivity of serologic testing also considerably decreases late in the course of the disease and in patients with calcified lesions. Conversely, asymptomatic patients commonly have seropositive EITB results.

In most patients, neuroimaging findings are not pathognomonic for NCC. If an eccentric scolex is seen within the cyst, NCC may be diagnosed confidently. Neither CT scans nor MRI images are practical for screening a large population for NCC, particularly in developing countries.

Cerebral angiography may be useful in the evaluation of vasculitis resulting from cisternal NCC. Narrowing, occlusion, and the beading of vessels may be seen. Angiographic findings of vasculitis are nonspecific and may be seen in cases of tubercular meningitis, chronic meningitis, and vasculitis related to collagen vascular disease.

Guidelines

The Infectious Disease Society of America (ISDA) and the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (ASTMH) have published joint guidelines for the diagnosis and management of NCC. The guidelines note that while there is a wide range of clinical manifestations of neurocysticercosis, the 2 most common clinical presentations include seizures and increased intracranial pressure (IP). The initial evaluation should include careful history and physical examination and neuroimaging studies. The guidelines recommend both brain MRI and a noncontrast CT scan for classifying patients with newly diagnosed neurocysticercosis. Additional imaging recommendations include the following

:

MRI should be repeated at least every 6 months until resolution of the cystic component or cystic lesions for patients with single enhancing lesions (SELs).

MRI in patients with seizures or hydrocephalus and only calcified parenchymal NCC on CT.

MRI with 3D volumetric sequencing to identify intraventricular and subarachnoid cysticerci in patients with hydrocephalus and suspected NCC.

Content.