Practice Essentials

Abdominal wall hernias are among the most common of all surgical problems. Knowledge of these hernias (usual and unusual) and of protrusions that mimic them is an essential component of the armamentarium of the general and pediatric surgeon. More than 1 million abdominal wall hernia repairs are performed each year in the United States, with inguinal hernia repairs constituting nearly 770,000 of these cases; approximately 90% of all inguinal hernia repairs are performed on males.

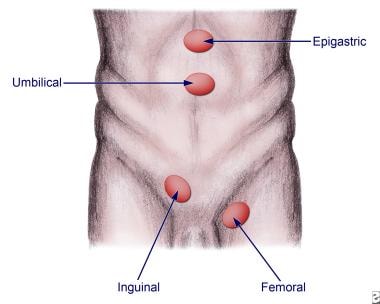

See the image below.

Anatomic locations for various hernias.

Signs and symptoms

Hernias may be detected on routine physical examination, or patients with hernias may present because of a complication associated with the hernia.

Characteristics of asymptomatic hernias are as follows:

Swelling or fullness at the hernia site

Aching sensation (radiates into the area of the hernia)

No true pain or tenderness upon examination

Enlarges with increasing intra-abdominal pressure and/or standing

Characteristics of incarcerated hernias are as follows:

Painful enlargement of a previous hernia or defect

Cannot be manipulated (either spontaneously or manually) through the fascial defect

Nausea, vomiting, and symptoms of bowel obstruction (possible)

Characteristics of strangulated hernias are as follows:

Patients have symptoms of an incarcerated hernia

Systemic toxicity secondary to ischemic bowel is possible

Strangulation is probable if pain and tenderness of an incarcerated hernia persist after reduction

Suspect an alternative diagnosis in patients who have a substantial amount of pain without evidence of incarceration or strangulation

When attempting to identify a hernia, look for a swelling or mass in the area of the fascial defect, as follows:

For inguinal hernias, place a fingertip into the scrotal sac and advance up into the inguinal canal

If the hernia is elsewhere on the abdomen, attempt to define the borders of the fascial defect

If the hernia comes from superolateral to inferomedial and strikes the distal tip of the finger, it most likely is an indirect hernia

If the hernia strikes the pad of the finger from deep to superficial, it is more consistent with a direct hernia

A bulge felt below the inguinal ligament is consistent with a femoral hernia

Characteristics of various hernia types include the following:

Inguinal hernia – Bulge in the inguinal region or scrotum, sometimes intermittent; may be accompanied by a dull ache or burning pain, which often worsens with exercise or straining (eg, coughing)

Spigelian hernia – Local pain and signs of obstruction from incarceration; pain increases with contraction of the abdominal musculature

Interparietal hernia – Similar to spigelian hernia; occurs most frequently in previous incisions

Internal supravesical hernias – Symptoms of gastrointestinal (GI) obstruction or symptoms resembling a urinary tract infection

Lumbar hernia – Vague flank discomfort combined with an enlarging mass in the flank; progressive protrusion through lumbar triangles, more commonly through the superior (Grynfeltt-Lesshaft) triangle than through the inferior (Petit); not prone to incarceration

Obturator hernia – Intermittent, acute, and severe hyperesthesia or pain in the medial thigh or in the region of the greater trochanter, usually relieved by thigh flexion and worsened by medial rotation, adduction, or extension at the hip

Sciatic hernia – Tender mass in the gluteal area that is increasing in size; sciatic neuropathy and symptoms of intestinal or ureteral obstruction can also occur

Perineal hernias – Perineal mass with discomfort on sitting and occasionally obstructive symptoms with incarceration

Umbilical hernia – Central, midabdominal bulge

Epigastric hernia – Small lumps along the linea alba reflecting openings through which preperitoneal fat can protrude; may be adjacent to the umbilicus (umbilical hernia) or more cephalad (ventral hernia [epiplocele])

See Presentation for more detail.

History and physical examination remain the best means of diagnosing hernias. The review of systems should carefully seek out associated conditions, such as ascites, constipation, obstructive uropathy, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and cough.

Diagnosis

Laboratory studies include the following:

Stain or culture of nodal tissue

Complete blood count (CBC)

Electrolytes, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), and creatinine

Urinalysis

Lactate

Imaging studies are not required in the normal workup of a hernia. However, they may be useful in certain scenarios, as follows:

Ultrasonography can be used in differentiating masses in the groin or abdominal wall or in differentiating testicular sources of swelling

If an incarcerated or strangulated hernia is suspected, upright chest films or flat and upright abdominal films may be obtained

Computed tomography (CT) or ultrasonography may be necessary if a good examination cannot be obtained, because of the patient’s body habitus, or in order to diagnose a spigelian or obturator hernia

See Workup for more detail.

Management

Nonoperative therapeutic measures include the following:

Trusses

Binders or corsets

Hernia reduction

Topical therapy

Compression dressings

Surgical options depend on type and location of hernia. Basic types of inguinal hernia repair include the following:

Bassini repair

Shouldice repair

Cooper repair

Simple inguinal hernia repair in children

Surgical approaches to other hernia types may vary, as follows:

Umbilical hernia – After exposure of the umbilical sac, a plane is created to encircle the sac at the level of the fascial ring, and the defect is closed transversely with interrupted sutures; if the defect is very large (>2 cm), mesh may be required

Epigastric hernia – A small vertical incision directly over the defect is carried to the linea alba, and incarcerated preperitoneal fat is either excised or returned to the properitoneum; the defect is closed transversely with interrupted sutures

Spigelian hernia – A transverse incision over the hernia to the sac allows dissection to the neck, and clean approximation of the internal oblique muscle and the transversus abdominis followed by closure of the external oblique aponeurosis completes the repair

Interparietal hernia – Large interparietal hernias require mesh or component separation technique

Supravesical hernia – The standard techniques for inguinal and femoral hernias are used, usually via a paramedian or midline incision

Lumbar hernia – A skin-line oblique incision is made from the 12th rib to the iliac crest; a layered closure or mesh onlay for large defects is successful

Obturator hernia – Generally approached abdominally and often amenable to laparoscopic repair; mesh closure is necessary for a tension-free repair

Sciatic hernia – A transperitoneal approach is used in the event of incarceration; a transgluteal repair can be used if the diagnosis is established and the intestine is clearly viable

Perineal hernia – A transabdominal approach with prosthetic closure is preferred; a combined transabdominal-perineal approach can also be used

Gastroschisis and omphalocele – Primary closure of fascia and skin is usually best; nonoperative management of gastroschisis (plastic closure) is an alternative to conventional primary operative closure or staged silo closure

Femoral hernia – A standard Cooper ligament repair, a preperitoneal approach, or a laparoscopic approach may be used; the procedure includes dissection and reduction of the hernia sac and obliteration of the defect in the femoral canal by approximating the iliopubic tract to the pectineal (Cooper) ligament or by using a mesh

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.