Practice Essentials

Head injury can be defined as any alteration in mental or physical functioning related to a blow to the head (see the image below). According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), more than 50,000 individuals die from traumatic brain injuries each year in the United States. Almost twice that many people suffer permanent disability. In the United States in 2013, about 2.8 million emergency department (ED) visits, hospitalizations, or deaths were associated with TBI—either alone or in combination with other injuries.

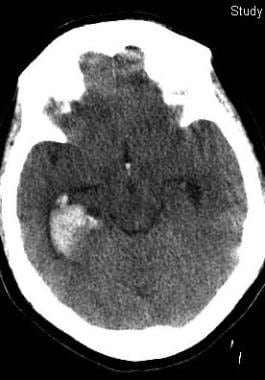

This 50-year-old woman with epilepsy seized and struck her head. Her initial Glasgow Coma Scale score was 12. Her scan shows prominent right temporal bleeding. She recovered to baseline without surgery.

Signs and symptoms

The Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) is the mainstay for rapid neurologic assessment in acute head injury. Following ascertainment of the GCS score, the examination is focused on signs of external trauma, as follows:

Bruising or bleeding on the head and scalp and blood in the ear canal or behind the tympanic membranes: May be clues to occult brain injuries

Anosmia: Common; probably caused by the shearing of the olfactory nerves at the cribriform plate

Abnormal postresuscitation pupillary reactivity: Correlates with a poor 1-year outcome

Isolated internuclear ophthalmoplegia secondary to traumatic brainstem injuries: Has a relatively benign prognosis

Cranial nerve (CN) VI palsy: May indicate raised intracranial pressure

CN VII palsy: May indicate a fracture of the temporal bone, particularly if it occurs in association with decreased hearing

Hearing loss: Occurs in 20–30% of patients with head injuries

Dysphagia: Raises the risk of aspiration and inadequate nutrition

Focal motor findings: Include flexor or extensor posturing, tremors and dystonia, impairments in sitting balance, and primitive reflexes; may be manifestations of a localized contusion or an early herniation syndrome

See Clinical Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

Bedside cognitive testing

In the acute setting, measurements of the patient’s level of consciousness, attention, and orientation are of primary importance.

Some patients acutely recovering from head trauma demonstrate no ability to retain new information. Mental status assessments have validated the prognostic value of the duration of posttraumatic amnesia; patients with longer durations of posttraumatic amnesia have poorer outcomes.

In the long-term setting, the following bedside cognitive tests can be employed:

Mini-Mental State Examination

Luria “fist, chop, slap” sequencing task: To rapidly assess motor regulation

Antisaccade task: Impaired in patients with symptomatic brain injury; the sensitivity of this test in detecting brain injury has been questioned

Letter and category fluency: To provide information about self-generative frontal processes.

Untimed Trails B test: Allows further qualitative testing of frontal functioning

Laboratory studies

Sodium levels: Alterations in serum sodium levels occur in as many as 50% of comatose patients with head injuries

; hyponatremia may be due to the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone (SIADH) or cerebral salt wasting; elevated sodium levels in head injury indicate simple dehydration or diabetes insipidus

Magnesium levels: These are depleted in the acute phases of minor and severe head injuries

Coagulation studies: Including prothrombin time (PT), activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), and platelet count; these are important to exclude a coagulopathy

Blood alcohol levels and drug screens: May help to explain subnormal levels of consciousness and cognition in some patients with head trauma

Renal function tests and creatine kinase levels: To help exclude rhabdomyolysis if a crush injury has occurred or marked rigidity is present

Neuron-specific enolase and protein S-100 B: Although earlier studies suggested that elevated serum levels may correlate with persistent cognitive impairment at 6 months in patients with severe or mild head injuries, current opinion considers these tests no longer useful.

In 2018, a commercially available blood test for mild brain injury was approved by the FDA.

This test reportedly identifies 98% of patients with abnormal head CT scans.

Imaging studies

Computed tomography scanning: The main imaging modality used in the acute setting

Magnetic resonance imaging: Typically reserved for patients who have mental status abnormalities unexplained by CT scan findings

Electroencephalography

Although certain electroencephalographic patterns may have prognostic significance, considerable interpretation is needed, and sedative medications and electrical artifacts are confounding. The most useful role of electroencephalography (EEG) in head injuries may be to assist in the diagnosis of nonconvulsive status epilepticus.

See Workup for more detail.

Management

Intracranial pressure

If the intracranial pressure rises above 20-25 mm Hg, intravenous mannitol, cerebrospinal fluid drainage, and hyperventilation can be used. If the intracranial pressure does not respond to these conventional treatments, high-dose barbiturate therapy is permissible.

Another approach used by some clinicians is to focus primarily on improving cerebral perfusion pressure as opposed to intracranial pressure in isolation.

Decompressive craniectomies are sometimes advocated for patients with increased intracranial pressure refractory to conventional medical treatment.

Hypertonicity

Dantrolene, baclofen, diazepam, and tizanidine are current oral medication approaches to hypertonicity. Baclofen and tizanidine are customarily preferred because of their more favorable side-effect profiles.

Subdural hematomas

Traditionally, the prompt surgical evacuation of subdural hematomas was believed to be a major determinant of an optimal outcome. However, research indicates that the extent of the original intracranial injury and the generated intracranial pressures may be more important than the timing of surgery.

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.